How do I get better at ASL? I see this question asked many times. I have answered it many times but never to the depth which I am doing here. It is my belief that anyone can get better at ASL, particularly in rules knowledge and understanding of the game’s mechanics. While understanding the rules might not lead to being in the top 10 percent of all players, it will lead to winning more games. After all, tactics are “the art or skill of employing available means to accomplish an end”. A better understanding of the rules makes more “means” available and creates more opportunities to win. It still falls on the player to understand how to employ the means, but that comes with experience.

Let’s look at my approach to getting better at ASL.

Read the Rules

I have played many of the world’s top players. Each of these players brings an interesting viewpoint to the game. All of them will put you to the test. The common thread among all of them is they know the rules VERY well. This means they have options available to them you just don’t know about because you aren’t well versed enough in the rules to realize it is an option. Even when you know about the rule, chances are they have interesting or unique ways of employing the capability you haven’t thought of. Don’t take it personally. We have all been there. To cope with this, take notes. But if you want to get better, you have to read the rules.

Play Better Players

These guys just know more than you do. They win because they are better at employing the rules and capabilities than you are. And chances are, they got where they are by playing someone better than they were early in their ASL career.

Don’t just sit in awe of what they do, ask them why they did it. Rarely is there no reason for something. They have a plan and everything they do is working towards completing that plan. Take notes (don’t slow the game!). Jot down rules you learn. If you can, take regular pictures of the board so you can look at it later. Ask them to speak about how you set up and what they gleaned from it. These guys are invaluable teachers. Learn from them.

Just expect to lose a lot. I know Fortenberry beat me like a drum (and still does).

Take Notes

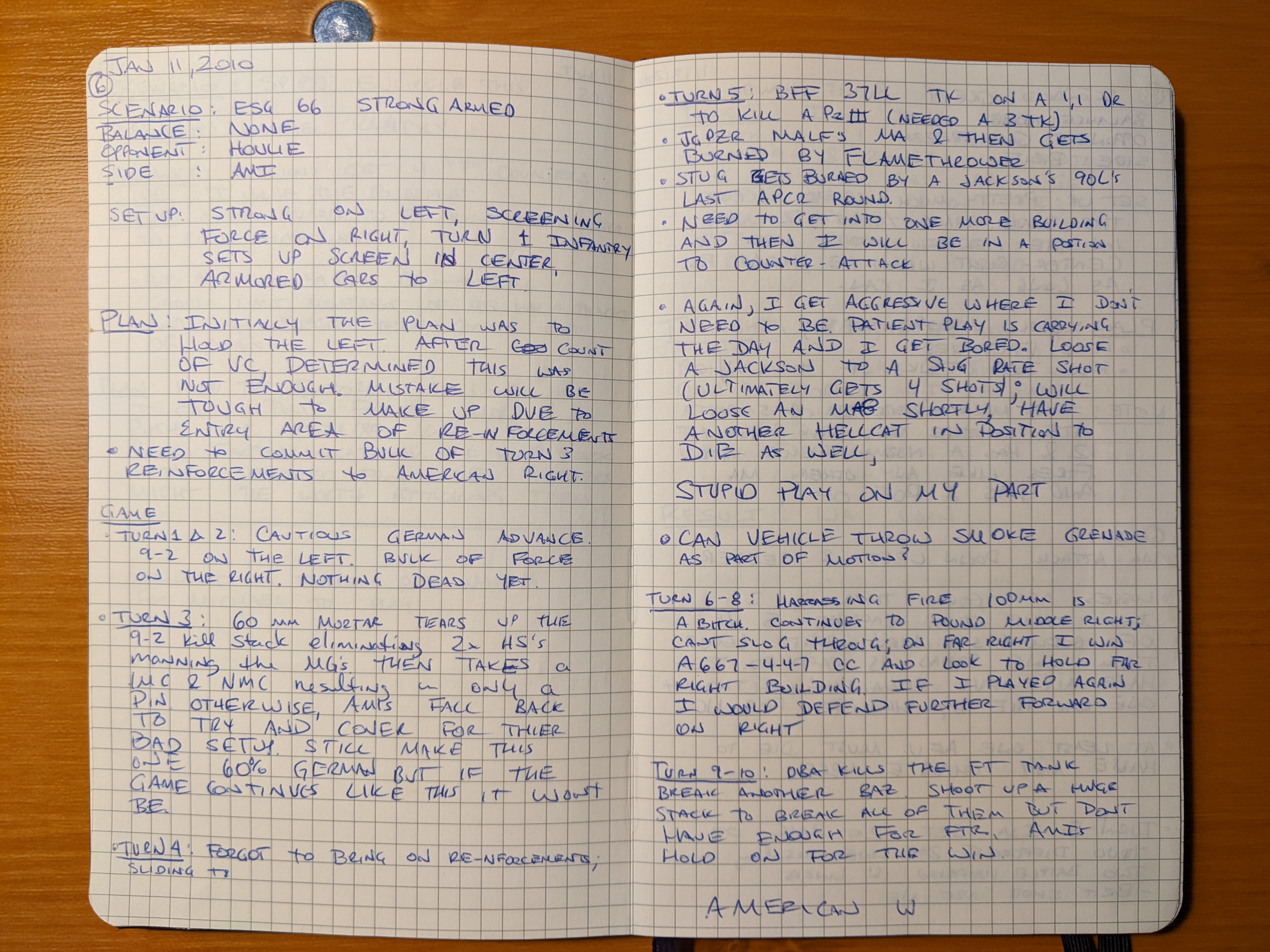

I encourage you as a player to take notes. IMO, it is one of the best ways to improve your overall play. Just capture what works for you. Even 12+ notebooks into it–covering close to 3000 scenarios played–my note-taking process is constantly developing. It’s important to note, though, you can’t let this slow the game down.

Over the years, I have kept notes on all my ASL scenarios played in a series of Moleskine Notebooks. I currently have 12 full and I am working on my 13th. These notebooks record thoughts on how I planned to attack or defend. I might jot down a rules reference for something I learned or expect might come up in play. Personally, I have a much higher chance of learning and internalizing something if I take the time to write it down. Anyone who has ever played ASL with me will probably remember my notebook. To be fair, I picked up this habit very early from JR Tracy. His notebooks lead to his legendary AARs.

Earlier in my ASL career, I was more fastidious in note taking than I am today. Comparatively speaking, I had more to learn and think about as I developed my ASL chops. If you could see my earlier note taking, you would see my notes were more organized, more in-depth, more thought out. As I was correspondingly focused on learning, my notes reflected this. I wrote neat tricks players taught me (Hi VBM freeze, nice to meet you) or rules I learned (MG TH/TK attempts do not cower and are a nice way to lay down key firelanes). I captured the scenario I played, notes on each side’s setup, who won, who lost, who got the critical DRs at the critical moment. For me, all of this plays into my post-game processing.

These days, I am comparatively more experienced. There are fewer rules to learn, fewer situations I haven’t seen, and fewer applications of the rules I haven’t seen. Still, I am occasionally caught out and I make an entry in my notebook.

Discuss What Happened After The Game

At last, we come to the post-game. All the dice rolled in anger are gone. We sit at the table, victorious or vanquished, but our work is not over yet. To get better, we must learn the lessons our game just taught us. This is an effort. One you must undertake unless you are just gifted, and even gifted players can improve their game through effort. The best time to reinforce learning is right after the lesson. We can glean some of this learning from our opponent, and some will have to be pulled from our own wits.

These post-game chats are one of the most significant effects of playing broadly. The more people you play with, the more opinions you can solicit and adapt to your play style. Not everything you see is going to work for you. But soliciting viewpoints from many people can help you distill an argument down to a concept that works for you.

What Should We Talk About

Initially begin your post-game by asking your opponent what you did right and what you did wrong in his opinion. Ask him to describe how you did from his point of view. From his point of view, you can subsequently learn where you applied the most pressure and where you might have done better. Further, ask why he placed his key SWs and major assets where he did. Find out what his plan was to begin with and how he adapted it as the game went along. Try to determine who had the better fortune and how that fortune affected the game. Not all double ones are created equal. Even a double six can be lucky if it clears all the SMOKE, obscuring your objective on the penultimate turn.

Next, speak about your plan and how you subsequently adapted it as the game progressed. Speak about why you decided as you did and seek your opponent’s opinion on your thinking. How did his play influence your approach? How did your play influence him?

The key to learning in ASL is to try to identify the cause and effect. At its heart, winning is about influencing your enemy into a losing position. You can do this through firepower, maneuver, cracking your opponent’s Personal Morale Check (my personal weakness), or a combination of all three. Indeed, what matters is you find a way to victory.

Thinking About Learning For a Moment

So you set up a game with a friend. Read the rules that needed reading. Jotted down some thoughts on the upcoming game. Made your plan and executed it. Took some notes along the way. Chatted about it afterwards but now what?

Everything we have done up to this point has set the stage for learning. To complete the process, you must make an effort. I am not suggesting you take an hour to write a five-page entry into your notebook. You can focus on one or two things you took from the game you just played. What new rule did you learn? What new tactic did you see? Record these into your notebook. Take this one last chance to hammer home the lesson. Learning is an active process.

There is a theory that humans fall into one of four classes of learners: visual, auditory, reading/writing, and kinesthetic. As humans, we all have differing talents, but for learning, multimodal learning seems to work best. The good news for us ASL players is our game ticks off many (all?) of these modes. The game itself is very visual. It has a spatial and temporal resolution to it. The rules and our post game notes hit the reading/writing target. ASL is a hands-on game, hitting the kinesthetic–learning by doing–target. Chatting with our opponent ticks off the auditory. I include on-line discussion forums in the auditory column. Online discussion is a modern form of interpersonal communication, which is what “auditory” embodies in this learning model.

Self Reflection

Once the chatting is done and the pieces are put away, take a moment to look back on your notes. How accurate were you in predicting what your opponent did? How did your initial play work? What adaptations did you make to your plan as the scenario developed?

Still, the more effort you put into learning, the better player you will be in all aspects of the game. When you get good enough at it, you no longer need to think about game mechanics, they just happen as a thing you do out of habit. This allows you to reserve your thinking for things we haven’t seen before and for adapting as the situation develops. Your thinking stops being about how the game works and morphs into how do I apply the mechanics to achieve an outcome. Walking this all the way back to the first paragraph, you are using “the art or skill of employing available mechanics to accomplish the VC;” AKA tactics.

Conclusion

I really hope this gives new players the confidence that they can improve. It is a process. It doesn’t happen without some level of effort on your part. Fortunately, playing widely and as often as you can is a part of that process. It isn’t all tedious and you can make good friends along the way. We won’t all end up winning tournaments or topping the ASL Player Ratings, but getting better at ASL doesn’t require us to. Competent play is its own destination. I hope this helps in some small way. – jim

Thanks Jim, interesting piece. Variation on a theme: for some time I’ve kept a Rules Reminder List (Word document). This started as purely that – rules I found it hard to remember – but has evolved to include tips, techniques and tactics. It now even includes a couple of Q&A’s on things that others frequently get wrong (e.g. C6.5-51: a ½” acquisition counter MUST track a target that moves whilst it remains in the firer’s LOS).

Needless to say the list is continually growing, but it’s useful both in-game and as a ‘refresher’, for example before a tournament.

Wow, Jim, just wow. One question I have about the notebooks. How far back do you go into your notebooks in the process of using them? Do you do some kind of indexing of what is written in them.

They are in storage in the US. I don’t know exactly how far back they go but it is probably 25 years. I have two of them here, the one I was working on when I left and the new I started.

In the early days, there was no indexing. Now I tend to leave a page at the front blank and put some sort of note in the front of particularly memorable games. I also put the date range the book covers inside the front cover.

I used to play a lot more so a notebook didn’t last much more than 2 years. Now that I am playing less, they can last 4 or 5 years.